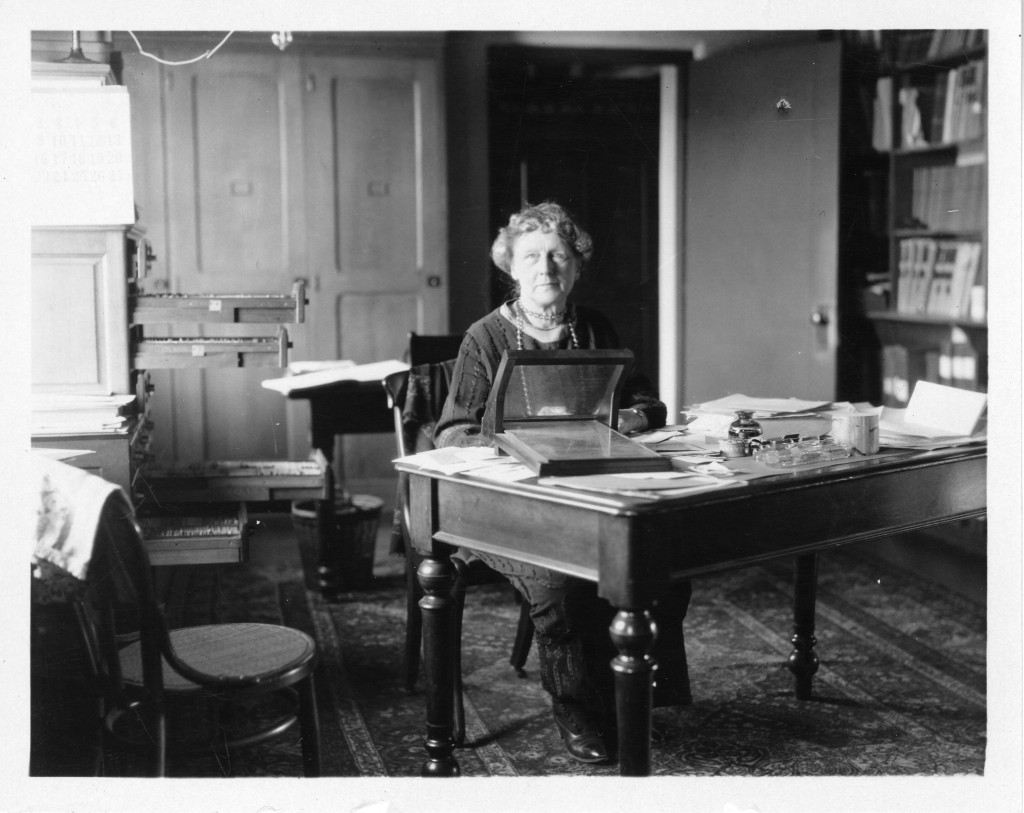

I’ve been poking around the Harvard Library’s digital archives quite a bit this week, preparing for a “Genius Day” workshop I’m leading next month with the Institute for Educational Advancement. The focus of the workshop is Annie Jump Cannon, an astronomer famous for developing the stellar classification scheme still used today and for personally classifying hundreds of thousands of stars by their spectra. While trying to track down a high-resolution scan of one of Cannon’s spectroscopic plates,1 I came across an article she wrote in the Radcliffe Quarterly in 1931 entitled “Astronomical Adventures.” In recounting some of her experiences, she describes a field “at a cross-roads between the old, the visual, and the new, the photographic method,” and offers a new definition for the “adventures” in store for aspiring astronomers. I thought I’d share a few brief excerpts that I particularly enjoyed, but feel free to read the entire account here. 2

I’ve been poking around the Harvard Library’s digital archives quite a bit this week, preparing for a “Genius Day” workshop I’m leading next month with the Institute for Educational Advancement. The focus of the workshop is Annie Jump Cannon, an astronomer famous for developing the stellar classification scheme still used today and for personally classifying hundreds of thousands of stars by their spectra. While trying to track down a high-resolution scan of one of Cannon’s spectroscopic plates,1 I came across an article she wrote in the Radcliffe Quarterly in 1931 entitled “Astronomical Adventures.” In recounting some of her experiences, she describes a field “at a cross-roads between the old, the visual, and the new, the photographic method,” and offers a new definition for the “adventures” in store for aspiring astronomers. I thought I’d share a few brief excerpts that I particularly enjoyed, but feel free to read the entire account here. 2

Astronomers are not often thinking of pure discovery. We have no expectations of ever finding at one glance, as did Tycho Brahe, a new star rivaling Venus in brilliancy, nor any hope of emulating Galileo’s thrilling experiences. Something different must satisfy us in these later days.

Astronomers are not often thinking of pure discovery. We have no expectations of ever finding at one glance, as did Tycho Brahe, a new star rivaling Venus in brilliancy, nor any hope of emulating Galileo’s thrilling experiences. Something different must satisfy us in these later days.

Has it not been something of an adventure to take any part, however small, in the remarkable development of astronomy during the present century?

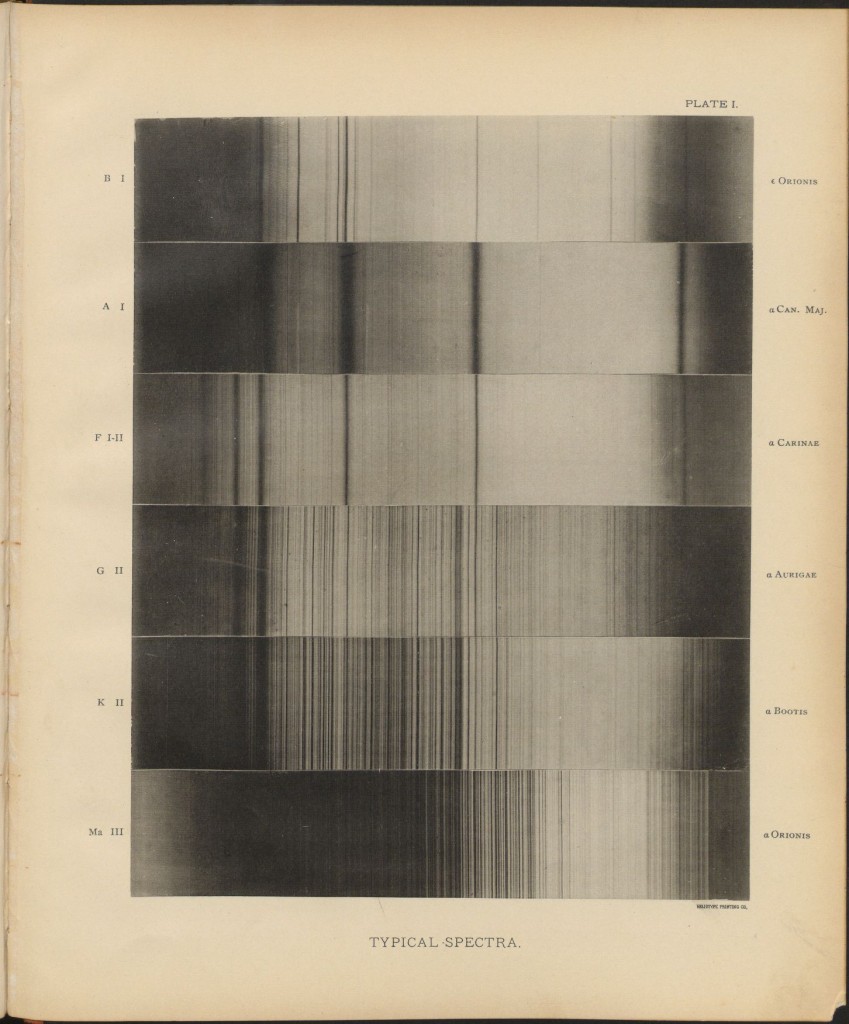

It is often difficult when one stands at the cross-roads to choose the new and untrodden path. It is not the path of our dreams. Who in the “gay nineties” ever dreamed of an astronomer who was not nightly gazing through a large telescope at soul-thrilling celestial objects? Time has proved, however, that along the new and seemingly unromantic photographic path lay all the coming adventures.

There is romance in science! What more appealing to the imagination than the fact that these dark lines in star light bring us messages as to what the stars are, how they are traveling, and how far away they are.

The spectrum of such a star, if it can only be obtained, always tells the story of its vagaries in the bright bands indicating glowing gases. Not soon to be forgotten was the thrill of finding such an object while in Arequipa, of eagerly photographing its spectrum and beholding on the negative the tell-tale bands proclaiming its escapade. To the gleaming southern stars, thus one was added, whose light had been traveling fifty thousand years to shine down on us over the Andes.

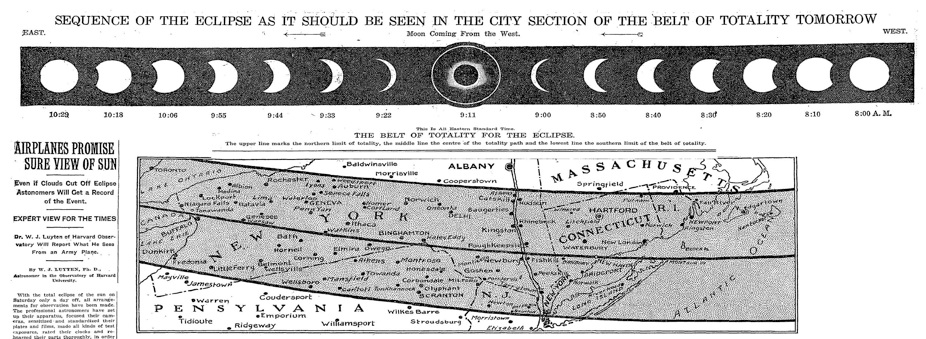

When the California astronomers came east to the eclipse of January 24, 1925, we could boast of no such optimistic weather reports, but almost contrary to our own expectations, we had a clear sky on that below zero morning. No clouds marred the spectacle from Cornell to Nantucket. The mystical shadow bands danced, glowing prominencies streamed out, and the glowing corona flashed forth its matchless beauty.

When the California astronomers came east to the eclipse of January 24, 1925, we could boast of no such optimistic weather reports, but almost contrary to our own expectations, we had a clear sky on that below zero morning. No clouds marred the spectacle from Cornell to Nantucket. The mystical shadow bands danced, glowing prominencies streamed out, and the glowing corona flashed forth its matchless beauty.

Curious, I looked around for other personal accounts from the women at Harvard College Observatory, the “computers” that were the backbone of Edward C. Pickering’s research program in the decades surrounding the turn of the 20th century. While not at all a comprehensive survey of the online archive’s content, my little search yielded a couple of items that I am truly happy to have come upon. I’ll do my best to share some of them here as well.

- Thanks to Jonathan McDowell and twitter, I now have many wonderful photographs of the Harvard plate stacks and Cannon’s spectroscopic work! ↩

- And for a very adventurous version of Cannon, check her out on Rejected Princesses! ↩