[NOTE: I started this blog about three months ago when the first episode of my web series came out on PHDtv, and around that same time I joined Twitter. I’d also just come back from my first ever non-science conference, the annual meeting of the History of Science Society in San Diego, and I was just beginning to feel comfortable describing myself as a scientist AND a historian of science (I’m still working on that comfort level). With one foot in either community, I’ve been rather sensitive over the past few months to conflicts, controversies, and misunderstandings between the two disciplines, and there have been a surprising number of them in so short a time. I’ve been meaning to collect my thoughts on that for a while, and now that I’ve started to do that it seems there are way too many thoughts for one post. So here’s my first post in a new category that I’ve decided to call “Reflections.”]

I was admitted to Caltech as a graduate student in planetary science in 2007, and sometime since then, in the midst of qualifying exams, conference abstracts and TA assignments, I discovered I had a hidden passion: history of science. I don’t know why it took me so long to figure it out. As an undergrad at MIT, my favorite classes were in the Literature department, and I took enough of them to have majored in it (sometimes I wish I had). My second home was the student club office of the Shakespeare Ensemble, and I kept participating in student theater after moving to Caltech to pursue my doctorate in planetary science. I audited language classes (Latin and French) and dropped out when my required coursework in continuum mechanics and geophysics got too intense.

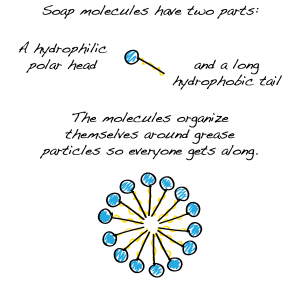

I always knew I loved science, but I didn’t always know that loving it and doing it aren’t necessarily the same thing. I thought my interest in the humanities and my interest in science were fundamentally incompatible, like oil and water, and I compartmentalized. I avoided science topics in my extracurricular activities and pretended I didn’t have hobbies (let alone time-intensive ones like theater and learning dead languages) in my science life.

Then one day while I was flipping through the course manual, I found out I could get a graduate minor in History and Philosophy of Science (there is an HPS department at Caltech, although there is no graduate program). I thought, “Hey, it’s just a minor – I can do that and maybe no one will mind since it’s about science.” Oil and water won’t mix if that’s all you put in the beaker, but add some soap and it’s a different story. I figured that history of science might just be my soap, so I registered for classes.

Already pretty good at fitting in extra coursework, I had no problem with “Intro to History of Science.” In fact, I was actually happy to write the first term paper. Stuck in the world of science journals for three solid years, I actually missed writing compound sentences and finding primary sources and building an argument to a conclusion. The counterpart class, “Intro to Philosophy of Science” was probably the best class I’ve taken at Caltech, and all in all I felt very happy to be part of a humanities community again.

It was a lot of extra work, but it felt right, and I’m not exaggerating when I say it completely changed the way I look at science, including and especially my own research. That part was unexpected. As a practicing scientist at a top-tier school, I went into that first HPS class pretty confident that I knew what science is and how it’s done. That’s not to say that I had articulated that to myself beforehand – actually, I think the first and biggest lesson I learned was that there are different ways of doing and thinking about science and it’s not something that “everyone just knows.” That might sound really astoundingly obvious, but I don’t think scientists are encouraged to think about it much in their training – I wasn’t. There’s a sense that the process is fixed and impartial; you do your work and if it turns out to be right, the scientific method will bear that out and the chaff will fall by the wayside. We like to think that we ourselves are irrelevant and it’s the evidence and the process that move things forward (hence the hideous passive tense of all those journal articles). Until I sat down in that classroom with about 18 new Caltech freshmen who signed up to fulfill a Hum requirement, I don’t think anyone had ever asked me “What is science?”

And I found it hard to answer.

That really tripped me up, and I was sold. I started looking into my options for continuing work in history of science, and even considered switching into it altogether. I talked to professors I knew about degree programs, job prospects, getting a second Ph.D. – anything I could think of that might help me “make up time,” having spent several years in grad school already. Then I heard about Daniel Kennefick. He graduated from Caltech in 1997 with a joint Ph.D. in Physics and History and Philosophy of Science. He wrote two full theses, had two committees, and (I think) one giant defense. Afterward, he did a couple of postdocs in history of science, published his history thesis as a book, and went back to physics and is now a full-time professor. While Caltech has no graduate program in any of the humanities subjects, it seems that it’s small enough to make some new rules if you have the right combination of resolve, talent, and charismatic advisors on your side (Kennefick’s was Kip Thorne). It’s maybe not quite the same as getting two separate Ph.D.s, but it gives me the option of finishing my science degree (which is very important to me) while also doing some real work and gaining credibility (well, hopefully) in history of science.

So that’s the plan. It hasn’t all been unicorns and rainbows, but I believe I can make it work. It’s not an easy thing to explain to my colleagues in planetary science (or even to my family, who I’m sure are wondering when I’ll graduate already) that a Ph.D. in science isn’t enough. On the other hand, people I’ve met in history of science fields have been surprisingly welcoming. I’ve spent a lot of time in the past few weeks trying to sort out exactly this interaction: how do scientists see historians and philosophers of science, and vice versa? And how do I fit in now? I worry a little that I’ll never fully be part of either community, that both sides will doubt me as a “serious researcher,” but that’s a post for another day. For now I’m happy to just let everyone (including me) get used to the idea that I can define myself in more than one way.

So that’s the plan. It hasn’t all been unicorns and rainbows, but I believe I can make it work. It’s not an easy thing to explain to my colleagues in planetary science (or even to my family, who I’m sure are wondering when I’ll graduate already) that a Ph.D. in science isn’t enough. On the other hand, people I’ve met in history of science fields have been surprisingly welcoming. I’ve spent a lot of time in the past few weeks trying to sort out exactly this interaction: how do scientists see historians and philosophers of science, and vice versa? And how do I fit in now? I worry a little that I’ll never fully be part of either community, that both sides will doubt me as a “serious researcher,” but that’s a post for another day. For now I’m happy to just let everyone (including me) get used to the idea that I can define myself in more than one way.

There’s another strand to this story that I’ve been avoiding, and it deserves its own post too. While I was going about my business taking classes for a graduate minor, the huge freight train of science communication (and commiseration) that is PHD Comics was barreling toward me, and in the fall of 2010 I was swept into The PHD Movie and all of its aftermath, which included the beginnings of PHDtv, my own web series True Anomalies (Tales from the History of Science), and this blog. Already balancing two academic lives, I suddenly had access to the world of science communication too. Can all three work together? Find out next time…

Greetings, fellow Techer!

I was a Caltech undergrad, and I often wish I’d taken better advantage of the Humanities department. Though to be honest, I think I needed the intellectual maturity of a couple of years in graduate school before I could appreciate the study of science in its historical and philosophical context.

I went through a bit of an intellectual crisis in the first year of my engineering PhD: if science is all about making logical deductions from experimental observation, why don’t people reach the same conclusions? Why do very smart people disagree with each other in cutting edge fields? How do I decide who to believe?

Then I read Thomas Kuhn and all was light :)

Thanks for the thoughtful comment, Bob. I get the impression that the Humanities department here at Caltech is a bit under-appreciated by most of the students (who, to be fair, are mostly here for science and engineering), and I think it would be awesome if new grad students were required to take a class in the philosophy of science. Maybe it would do us all good to have an intellectual crisis every once in a while!

I also agree that much of Kuhn’s Structure clicked with me the first time I read it, especially the description of ‘normal science’ (and yes, ‘anomalies’), but I wouldn’t say it’s the final word on how science works, and his ideas have been interpreted (and clarified) over the years (for example: Hoyningen-Huene’s Reconstructing Scientific Revolutions).

Interesting thought that history may be the soap that brings science and its human(itie)s together. A crucial element that defines soap [opera], however, is the continuous open-ended narrative. While that is surely true of the history of science (as science marches on:-) I wonder whether historians of science would find papers ending on a cliff-hanger palatable.

[…] Meg Rosenburg, “Between Science and HPS: How did I get here?,” True Anomalies: Tales from the History of Science, February 13, 2013, http://www.trueanomalies.com/between-science-and-hps/. […]

I just wanted to say how inspiring this blog of yours is!

I am in the final stretches of my own PhD studies (in maternal nutrition and fetal programming), and it has been such rocky road. I also know how difficult it is to hear the inevitable question of “When are you going to graduate?” come from family and friends.

I wanted to also say that I find the historical side of science to be an intriguing one, and I am so happy to have stumbled upon your blog (via PhD Comics).

Fantastic work, and awesome illustrations!

Cheers!